Digital Literacy Project

Digital Literacy Project (DigiLit) is a Harvard student organization and nonprofit that promotes one-to-one computing by initiating laptop pilot programs in elementary and middle schools around the globe. By developing training materials and curricula for teachers and students, DigiLit supports sustainable technology practices. The overall goal is to seamlessly integrate the XO into the classroom, so that it becomes a powerful tool for realizing creative potential.

The Cambridge Friends School is a small Quaker school in Cambridge, MA. The school has an extremely dedicated head of school and staff and an open-minded approach to education that often lends itself to experiments (like the one we are about to describe). CFS was founded in 1961 as a Pre-K to 8 co-educational institution, chartered by the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers) in Cambridge. CFS stresses their commitment to social justice, both to challenge oppression and to foster a diverse student and faculty population. The friendly, egalitarian culture is evident from the way students interact with teachers. In the classroom, students and teachers are on a first name basis.

At first glance, CFS doesn’t look like a school that would deserve an XO laptop pilot program. The school already has a laptop cart filled with PowerMacs, and most of the students have access to computers at home. But a laptop cart at school and computers at home do not constitute a 1-to-1 computing program that results in ownership of a laptop. CFS’s laptop cart made only guest appearances in the classroom and was primarily employed for internet research and word processing, rather than more creative endeavors.

At first glance, CFS doesn’t look like a school that would deserve an XO laptop pilot program. The school already has a laptop cart filled with PowerMacs, and most of the students have access to computers at home. But a laptop cart at school and computers at home do not constitute a 1-to-1 computing program that results in ownership of a laptop. CFS’s laptop cart made only guest appearances in the classroom and was primarily employed for internet research and word processing, rather than more creative endeavors.

When we began considering a pilot at an American school, we knew that a major barrier to entry would be teacher skepticism. Would we throw off standardized test scores and distract students with video games disguised as educational activities? After the head of CFS expressed enthusiasm about an XO pilot, we presented a project outline to all of the teachers at the school in order to dispel myths about 1-to-1 computing. The three sixth grade teachers enthusiastically agreed to begin training, so that their students could spend the spring semester with “the little green laptops.”

Over the course of the fall, we hosted training workshops with teachers, reviewed sixth grade syllabi, and brainstormed ideas for integrating the XO into the existing curriculum. In January, we worked with Olin College of Engineering and Illinois Math and Science Academy to continue teacher training and to offer laptop-based after-school activities for students during a pre-pilot week. We launched the pilot in mid-February with an XOXO Valentine’s themed party for CFS faculty, students, and families.

Over the course of the fall, we hosted training workshops with teachers, reviewed sixth grade syllabi, and brainstormed ideas for integrating the XO into the existing curriculum. In January, we worked with Olin College of Engineering and Illinois Math and Science Academy to continue teacher training and to offer laptop-based after-school activities for students during a pre-pilot week. We launched the pilot in mid-February with an XOXO Valentine’s themed party for CFS faculty, students, and families.

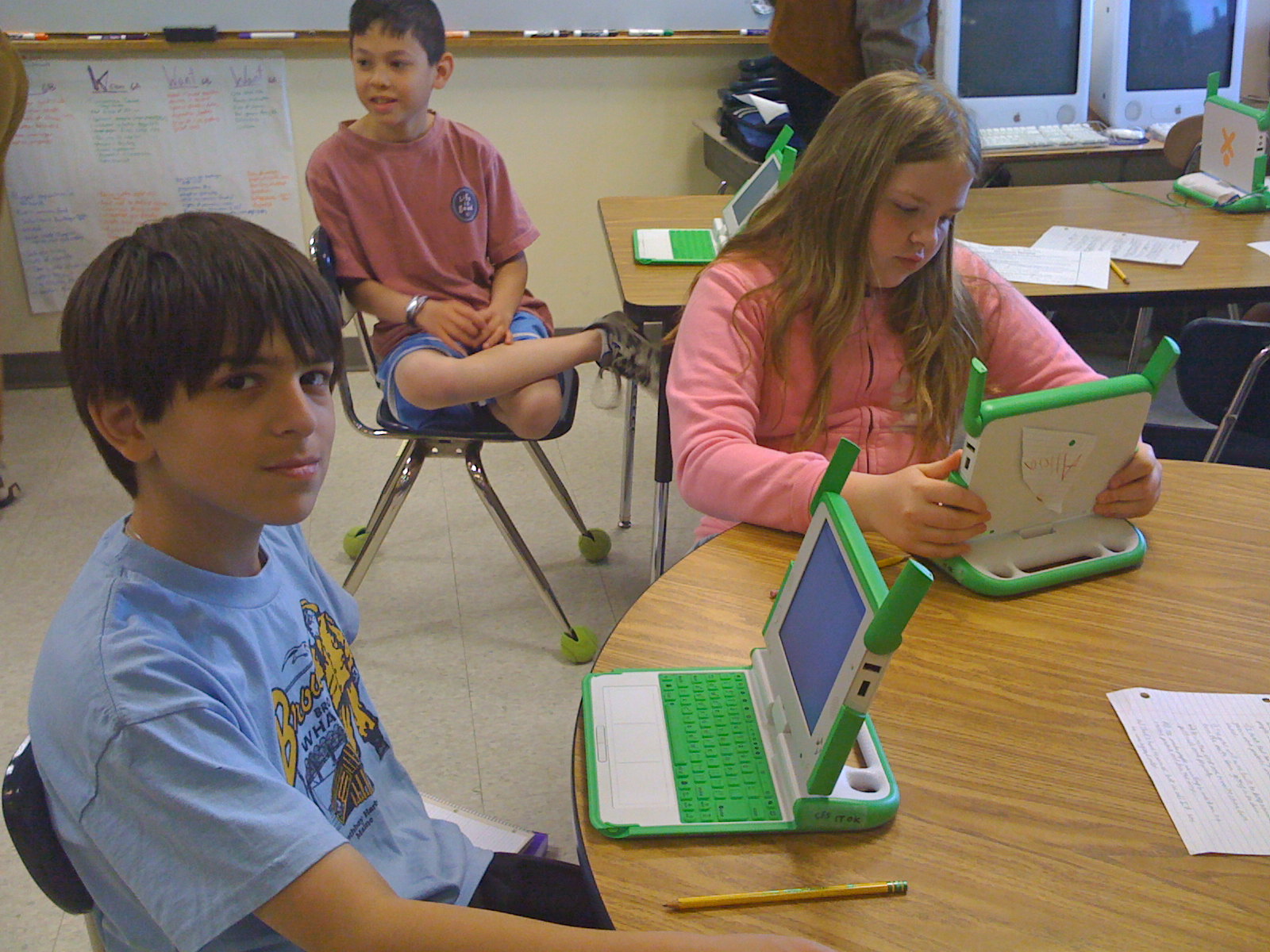

During the eight-week pilot, our team dually functioned as teaching assistants, helping to run lessons in the classroom, and ethnographic anthropologists, observing the changing student dynamic through video. Students picked up the XO’s unique operating system and software on the first day we introduced them to their new laptops. Eager spirits prompted most sixth graders to master the Record and Memorize activities, soon venturing to learn more obscure programs during free class periods.

Despite the positive momentum behind the pilot, it became clear that we had not adequately trained the three sixth grade teachers before bringing the XO into the classroom. Faced with planning an entirely new sixth grade curriculum as well as lessons that fully integrated XO activities into class time, the teachers felt uncomfortable using the XO for much more than internet research and word processing during their classes. We tried to alleviate these pressures by developing potential lesson plans and acting as in-class technical support, but we had not anticipated how difficult it would be to add a completely new tool to the classroom.

In many ways, the XOs replaced the laptop cart of PowerMacs—they were stored on a cart and kept at school overnight. Even though CFS’ open-mindedness towards new pedagogies was a major support for the pilot, the school’s strong emphasis on personal responsibility prevented students from taking ownership of the XOs. Recent irresponsible behavior with textbooks convinced teachers that students were unready to handle laptops, so the XOs were kept under lock and key at night.

After the initial honeymoon phase, students began to show frustration with any and all technical difficulties. During a collaborative biology activity, one student traded her XO for the shiny new MacBook she had in her backpack. Inherent in doing an XO laptop pilot at an American school is the idea that this is a waste, that privileged kids won’t get anything out of the XO. Midway through the pilot, we couldn’t help but wonder if we had proven this point.

After the initial honeymoon phase, students began to show frustration with any and all technical difficulties. During a collaborative biology activity, one student traded her XO for the shiny new MacBook she had in her backpack. Inherent in doing an XO laptop pilot at an American school is the idea that this is a waste, that privileged kids won’t get anything out of the XO. Midway through the pilot, we couldn’t help but wonder if we had proven this point.

But as the pilot continued into May, we started to see that students were more patient with technical glitches and more excited about mastering this new technology. During group activities, the XOs reinvented the concept of collaborative work, as students used the mesh network to chat and share links. Our interviews and qualitative studies indicate that the XOs facilitated a class-wide atmosphere of shared learning and communication.

Looking back, the dedicated sixth grade teachers wisely chose a slower but less artificial integration path for the XO. By using the XOs in the same way as the laptop cart, the teachers supported a more organic model for CFS. Although we would rather have sacrificed a laptop than stored all of them safely at school, we realize that any hesitancy on the part of CFS was not unwillingness to embrace a new learning tool. Rather, the school chose the less glamorous route: grow the nascent program slowly in order to build sustainable technology practices. In the future, we intend to continue to expand the comfort levels of teachers and students, as well as our own perceptions of learning. But we will always remember that even the most well-intentioned revolutions can lead to instability and defeat.

We are still finding ways to seamlessly incorporate the XO as a tool—like a pencil—instead of an afterthought. Can one ever truly bridge this gap? We’d like to think so. As we move forward with this project during the fall semester, we will continue to support one-to-one computing at CFS while simultaneously laying the foundation for a technology-based after-school program and homework clinic at a needier, inner-city school. Already, we have seen how schools’ reaction to our work has changed since we completed our spring study. Even though our program is not yet the key to breaking the MCAS code, we are still gaining a strong foothold in the Boston learning community.

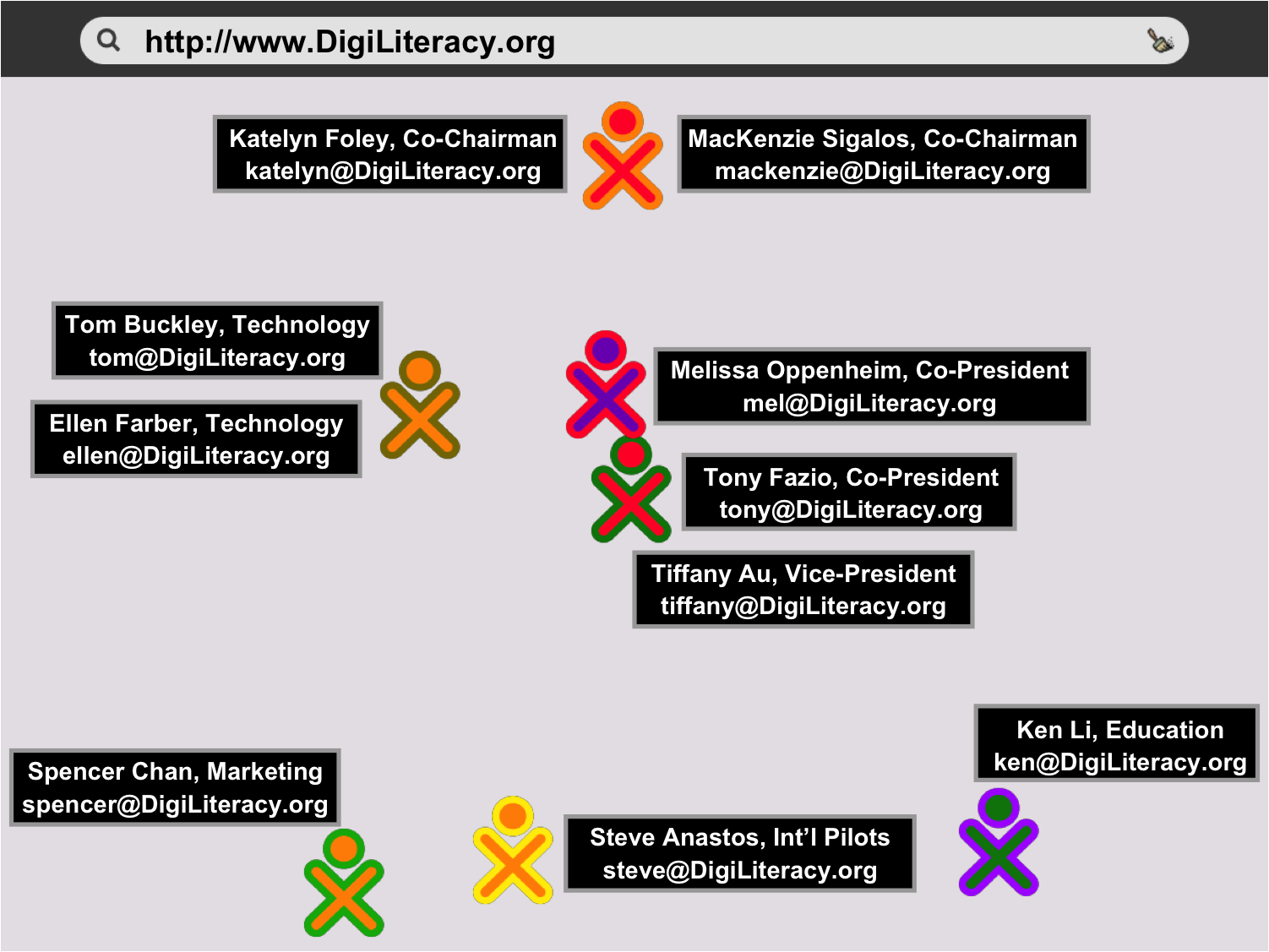

Submitted by Katelyn Foley (katelyn@DigiLiteracy.org) and MacKenzie Sigalos (mackenzie@DigiLiteracy.org)

Please check out our photos at http://www.flickr.com/photos/DigiLit. You can also find a preliminary report on our research, as well as XO tutorials and lesson plans at http://www.DigiLiteracy.org.